Imagine a world where human productivity isn’t just incrementally improved but explodes exponentially. This isn’t science fiction; it could become a reality if we tap into the potential within three levels of work: individuals, teams, and organizations, as outlined in this article. We’re operating at a fraction of our capacity, leaving a vast reservoir of human potential dormant.

This essay explores the factors contributing to this waste of human potential. The three follow-up articles will cover how large parts of this potential can be lifted to 100x your organization’s people performance, how data and AI will disrupt our work to become Future Work and finally how Future Work will change the role of HR.

The Individual: Not every moment of work is equal

At the individual level, potential is a function of knowledge, capabilities, and skills, as well as the ability to apply them effectively. This is particularly evident in complex fields like software development, where top performers can be up to 7x more productive than their average counterparts (Sackman, Erikson, & Grant, 1968). However, productivity isn’t evenly distributed throughout the workday. Often, it’s concentrated in “moments of truth” (Peters, 1987) – those instances of intense focus or flow, creative inspiration, critical decision-making, or high-stakes human interactions that disproportionately impact outcomes. Consider a designer’s breakthrough idea or a CEO’s pivotal strategic choice.

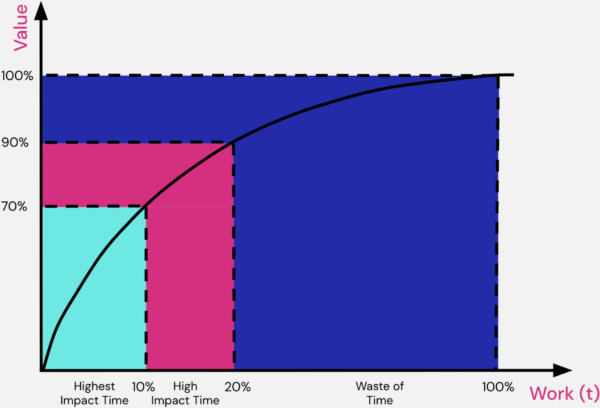

Picture 1: Distribution of Performance across Working Time

The distribution of value created during working time is diminishing exponentially. We roughly expect that with complex jobs,, a worker’s 10% most productive working time accounts for 60% to 80% percent of the total value created by this worker. We call this time “Highest Impact Time”. The following 10% of working time accounts for an additional 10% to 20% of the value created, summing up roughly 90% of the working time. That means that the rest of the working time, up to 80%, only contributes about 10% to 30% of the value of an employee. Compared to the High Impact Time, this literally is a Waste of Time.

But the modern workplace demands more than just applying technical skills at a high proficiency level at the right time. Accelerating innovation and change necessitates continuous learning, adaptability, and a “growth mindset” that embraces unlearning outdated knowledge as readily as acquiring new skills (Dweck, 2006). Foundational soft skills like communication, collaboration, and critical thinking are becoming increasingly vital.

Yet, many individuals struggle to thrive in this environment. The volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA) of the modern world, coupled with inadequate support from educational institutions and employers, can lead to diminished psychological safety, mental health challenges, and low engagement. Feeling adrift in a sea of constant change, many employees – an estimated 77% – are disengaged and seeking new opportunities (Gallup, 2023). This translates to a significant loss of individual potential, hindering personal growth and organizational success. Stress and health-related absence times are also increasing (IGES, 2023).

The Team: Synergies and Limitations

Teams offer a powerful mechanism for amplifying individual potential. Effective teamwork allows specialization across individual roles, strengths and preferences, shared learning, and synergistic outcomes surpassing individual efforts. The right team composition and a sound team density enable leveraged performance. However, team dynamics introduce their complexities, particularly in communication, coordination, and knowledge sharing. These challenges often limit adequate team size, as exemplified by the “2-Pizza Rule,” which suggests that ideal teams should be small enough to be fed by two pizzas (Bezos, 2018). But scaling work beyond traditional organisational and team boundaries, called “social composability” remains a largely unsolved task.

Despite these limitations, technology empowers teams with abundant resources and collaborative tools, enabling them to achieve unprecedented productivity levels. The rise of the “one-team unicorn” idea – small, highly effective teams (companies) achieving extraordinary results – highlights this potential. If we acknowledge these limitations but aim for great things to be achieved, team density and composition will become even more crucial in HR and management specialties. Besides this, unleashing the potential of high-performance teams requires overcoming challenges like social loafing, conflict, and a lack of psychological safety within the team.

Google’s Project Aristotle (Rozovsky, 2015) identified psychological safety as a critical factor in high-performing teams, leading to increased collaboration, innovation, and overall performance. The Standish Group’s CHAOS Report (2022) supports this, linking psychological safety and lower turnover to higher project success rates. Conversely, a lack of psychological safety can lead to decreased collaboration and innovation, resulting in missed opportunities and wasted potential within the team.

The Organization: Scaling for Efficiency leads to Stifling Innovation

Organizations, born from the Industrial Revolution and the principles of Taylorism, have traditionally focused on scaling for efficiency (Hagel, 2010) and optimizing predictable outcomes. While this hierarchical, bureaucratic structure has fueled economic growth and societal development, it often comes at the cost of individual and team potential.

| Number of Employees | Square Root of Employees | Employees Generating 50% of Output | Employees Generating Remaining 50% of Output | Percentage of Total Workforce Generating 50% of Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 10 | 10 | 90 | 10% |

| 1,000 | 31.62 | 32 | 968 | 3.2% |

| 10,000 | 100 | 100 | 9,900 | 1% |

| 100,000 | 316.2 | 316 | 99,684 | 0.32% |

Table 1: Price’s Law

Price’s Law, which states that the square root of an organization’s population produces 50% of its output (Price, 1963), illustrates this challenge. In a company of 100,000 (100) employees, just 316 (10) individuals are responsible for half the output. This highlights the disproportionate impact of a small group and the potential for wasted talent within larger workforces. There are multiple reasons for this, but most importantly, there are challenges in exponentially increasing complexity and lower levels of alignment relating to frictions of even gridlock in the status quo.

The “innovator’s dilemma” (Christensen, 1997) describes the phenomenon of lost innovation power, which suggests that large organizations optimized for efficiency struggle to adapt to disruptive change. This inherent inertia can stifle creativity and prevent organizations from fully leveraging their workforce’s innovative potential.

The Cost of Inertia: Quantifying the Wasted People Potential

To truly grasp the magnitude of squandered human potential, consider this: we are leaving a staggering amount of productivity on the table; Gallup’s State of the Global Workplace report for 2022 revealed that a mere 23% of employees are engaged at work, while a staggering 62% are emotionally detached, and 15% are actively disengaged (Gallup, 2023). This disengagement translates into lost productivity, with Gallup estimating it costs the global economy trillions of dollars annually. Furthermore, a study by McKinsey found that addressing factors like ineffective meetings and poor communication could unlock a 20-25% increase in productivity (McKinsey, 2022).

This vast reservoir of untapped potential stems from a confluence of factors. At the individual level, stress, burnout, and a lack of psychological safety hinder peak performance(Lee & Ashforth, 1996). At the team level, communication breakdowns, lack of trust, and ineffective collaboration stifle synergy and innovation (Rozovsky, 2015). And at the organizational level, rigid hierarchies, bureaucratic processes, and resistance to change impede agility and creativity (Deloitte, 2017).

We have created a table with some documentation of the waste of people potential by research.

| Criteria | Level | Measure of Wasted People Potential (KPI Impacted) | Source of the Measure | Percentage of Total Potential Wasted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Variation (Top vs. Average) | Individual | Productivity | Sackman, Erikson, & Grant, 1968 | Up to 6/7 (86%) |

| Moments of Truth | Individual | Value Creation | Picture 1 | Up to 80% |

| Disengagement | Individual | Productivity, Engagement | Gallup, 2021, 2022, 2023 | 80% (2021) and 77% (2023), Trend slightly recovering from Corona Pandemic |

| Stress, Mental Health, Absence days due to illness | Individual | Stress, Illness Days | Gallup, 2021, 2022, 2023, IGES 2024 |

Stress Symptoms 43% (2021) and 52% (2023), 5,5% Absence in Germany (Research and Consulting Organisations) |

| Job Insecurity, High Job Demands | Individual | Emotional Exhaustion, Burnout | Lee & Ashforth, 1996 | Not specified |

| Summary | Individual | +98,5% | ||

| Team Size, Composition, and Density | Team | Productivity, Performance, Quality | “Two-Pizza Rule” (Bezos, 2018) | Not specified |

| Conflict, Lack of Psychological Safety | Team | Turnover | Google’s Project Aristotle (Rozovsky, 2015), The Standish Group. (2022) |

10%-20% reduced turnover, 93%-125% higher project success rates |

| Lack of Trust, Ineffective Collaboration | Team | Synergy, Innovation | Google’s Project Aristotle (Rozovsky, 2015) | Fewer defects, more patents filed |

| Summary | Team | +60% | ||

| Price’s Law | Organization | Output | Price, 1963 | +99% from company size bigger than 1.000 employees |

| Innovator’s Dilemma | Organization | Adaptability, Innovation | Christensen, 1997 | Not specified |

| Ineffective Meetings, Poor Communication | Organization | Productivity | McKinsey, 2022 | 20-25% |

| Rigid Hierarchies, Bureaucracy, Resistance to Change | Organization | Agility, Creativity | Deloitte, 2017 | Not specified |

| Summary | Organization | +99% |

Table 2: Quantifying the wasted people potential

The 100x People Potential Opportunity: A Call to Action for People Data Collaboration

We provocate by using the “100x-people-potentia-opportunity” framing. This means we only use 1% of the existing potential, which is unrealistic based on our day-to-day experience. And even if the number was correct, how would it come close to lifting this potential?

However, if we only look at the table above, only one of the three levels of work can get us there; we are not talking about the potential on all three levels. And in many of the mentioned KPIs, we are experiencing a negative trend.

Of course, the individual contributions are somehow related, and there is also overlap between the levels, but we are in the area of two magnitudes of people’s potential.

How can this potential be addressed on each level? – individual, team, and organization. Here are some directions of thought to do so:

- Empowering Individuals: It is crucial to cultivate growth mindsets, provide continuous learning opportunities, and foster psychological safety. Organizations must prioritize employee well-being and create environments that encourage creativity and risk-taking.

- Optimizing Teams: Building high-performing teams requires careful attention to team composition, communication, and leadership. Organizations should empower teams with autonomy and resources while fostering a culture of collaboration and trust.

- Transforming Organizations: It is essential to move beyond traditional hierarchies and embrace agile structures that promote learning and adaptation in a “scalable for learning” mode (Hagel, 2010). Organizations must create a sense of belonging and purpose while fostering a culture of innovation and continuous improvement. Finally, the organization’s size in the future probably doesn’t have to be as big as today. Organizations might become smaller but better connected with other organizations, proliferating the organization’s boundaries.

The current state of human resources is often unambitious and ill-equipped to address these challenges profoundly. Traditional approaches to talent management, which are best practices and experience-focused, are struggling to keep pace with the increasingly changing nature of work and technology. Labor shortages, rapid technological advancements, and the shift towards scalable learning work demand a fundamental rethinking of the Human Resources fabric.

We can only sustainably and effectively achieve the above by systematically leveraging our people data to power insights, decisions, direction, and, ultimately, people AIs. This includes ways to collaborate about our people data across organizational boundaries.

We believe People Data Collaboration has the potential to move us beyond incremental improvements and embrace disruptive, positive-sum people data games.

Please stay tuned for the following two articles in this series to learn (1) how exactly we imagine People Data Collaboration can be a 100x game changer for HR and extend HR from experience- and best-practice-only mode to data- and AI-mode and (2) how Future Work in a world of AGI and algorithms might look like, including brain-computer-interfaced (BCI) digital brains and post-cognitive income.

This is the first article out of four published by Tapir. Here are the links to the other three articles:

Article 2: 100× Your Work With Positive-Sum People Data Games

Article 3: Future Work in a World of AI and Algorithms

Article 4: The Role of HR in a World of AI

Sources:

- Peters, J. (1987). Moments of Truth. Harper Perennial

- Bezos, J. (2018). The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon. Little, Brown and Company.

- Christensen, C. (1997). The Innovator’s Dilemma. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Deloitte. (2017). 2017 Global Human Capital Trends. Deloitte University Press.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Gallup. (2021, 2022, 2023). State of the Global Workplace: 2021, 2022, 2023 Report. Gallup, Inc.

- IGES (2024), Gesundsheitsstudie 2024, IGES Website

- The Standish Group. (2022). CHAOS Report.

- Hagel III, J., Brown, J. S., & Davison, L. (2010). The power of pull: How small moves, smartly made, can change everything. Basic Books.

- Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout.

- McKinsey. (2022). The overlooked essentials of productivity. McKinsey & Company.

- Price, D. J. de Solla (1963). Little Science, Big Science. Columbia University Press.

- Rozovsky, J. (2015). Psychological safety: The key to high-performing teams. Google re:Work.

- Sackman, H., Erikson, W. J., & Grant, E. E. (1968). Exploratory studies comparing online and offline programming performance. Communications of the ACM, 11(1), 3–11

Andreas Fauler

Business

What this is about

Unlocking untapped human potential in individuals, teams, and organizations can drive exponential productivity through growth mindsets, AI, and agility.Share Story!

Andreas Fauler

Business